“How am I not myself?” In I Heart Huckabees, Jude Law’s character poses this question to a pair of existential detectives. Until then, they have been unshakeable, but in response to his query, the two just stare at each other and repeat his words, profoundly and maniacally.

In real life, the question of identity—where we come from, who we are, who we want or need to be—is just as complicated and all-encompassing. Adrienne Dawes, a playwright and theater artist based in Austin, would tell you it’s also more fluid than we may be pressured to believe. Adrienne’s plays, especially her award-winning Am I White, reflect an interest in and exploration of identity that has its roots in her own experience. I recently got to chat with Adrienne, who is now busy with two simultaneous productions, Denim Doves and Love Me Tinder. In a phone call that felt like a connection between two friends who had yet to meet face-to-face, we talked about her productions, her day job, her unique family, meeting the man that Am I White was inspired by, the power and necessity of loneliness, and making stuff you love with people you love.

Since we’re just meeting, do you want to give me an overview of what you do, where you do it, and what projects are on your plate right now?

I am a playwright and a theater artist, and I live in my hometown of Austin, Texas. I moved around a bit because I went to school in New York and went to Sarah Lawrence, and I spent some time in Chicago, studying at Second City. Then I came back home. My family is all here. I come from a really unique family, so spending too much time away has not felt good. So I’m back here to be closer to them, and also the art scene here. I mean, talking about Austin is a whole other article. It’s definitely changing in some ways that are not so positive if you’re from here originally, but it’s still a place where you have your day job, but you have time to do your art.

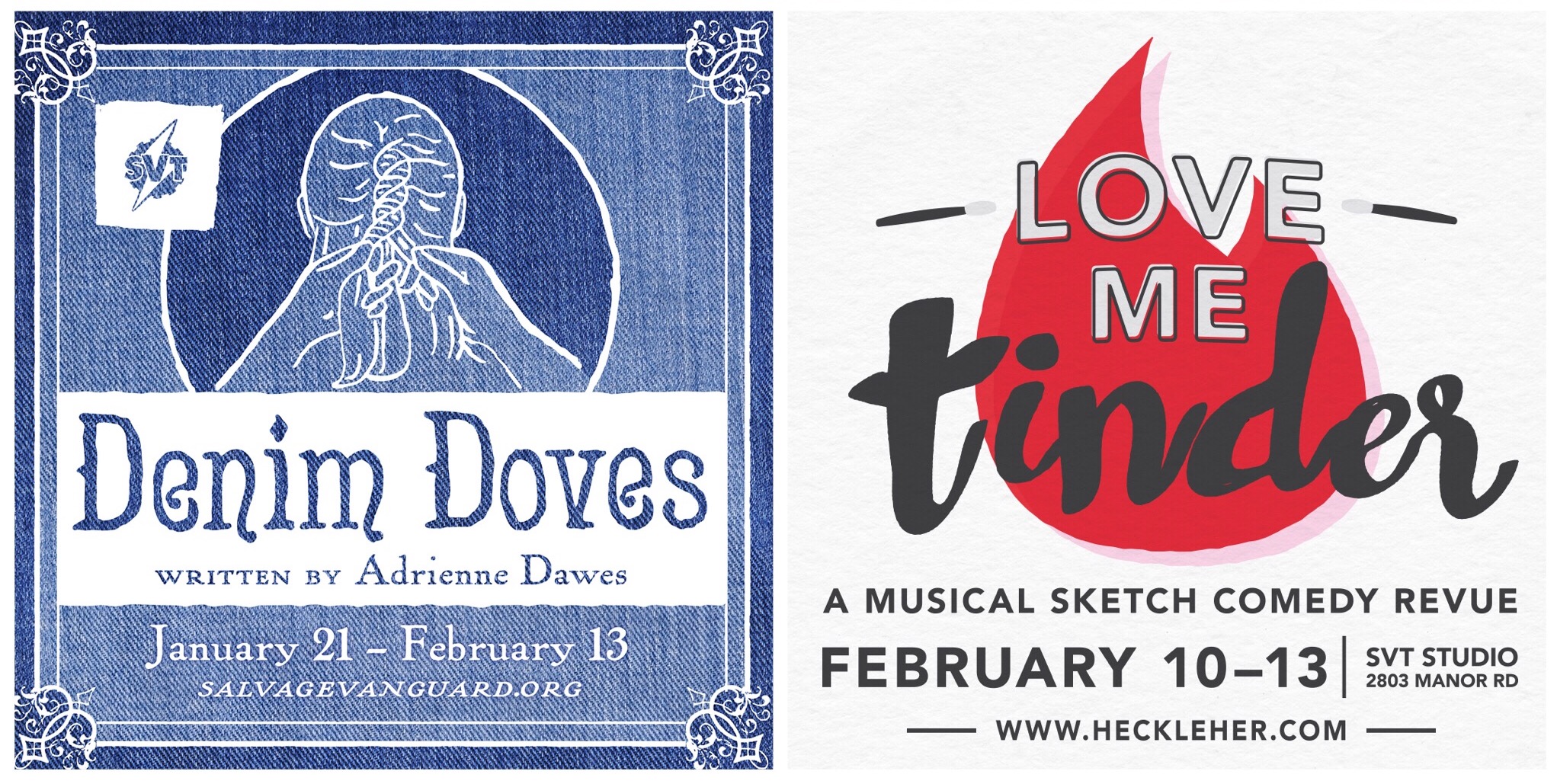

It’s a busy, busy time right now. I have two shows going on, kind of at the same time. I worked with Salvage Vanguard on a play called Denim Doves, and that’s on the main stage right now. It’s a futuristic, feminist farce. We talk about motherhood, fertility and woman’s identity and value in this sort of dystopian, crazy world. We are trying to use humor as a vehicle to talk about some more serious topics and our feminist rage [laughs] that we feel, especially being women that live in Texas. There’s a lot of stuff to be pissed off about, and you’re constantly reminded that your way of thinking is maybe not the majority.

Then, while that’s going on, I’m directing a show called Love Me Tinder, and that’s a musical sketch comedy about dating and relationships. I say it’s a popcorn show—it’s not going to save the world. [Laughs] It’s entertaining and fun. But the comedy community can be very white-washed and male-influenced, and you don’t see a lot of women or people of color in creative roles, so that’s something I’ve really been trying to push for; that’s a big motivating factor.

So…yeah! [Laughs] Somewhere in there, I sleep and eat and see my family. [Laughs]

You work a day job, too, right? What do you do by day?

In my day job, I work for a non-profit social services agency called Life Works. They’re in the community to help heal and help families stay together and be strong and meet their goals. I work in development, raising awareness and funds for them. I get to interact with some superstar counselors and case managers, and through that, I get to meet some of the clients, who have some really interesting stories. So there’s kind of an overlap there: in my artistic practice, I’m listening for stories and trying to find weird ways of interpreting what’s going on around me, and in my day job, I’m interacting with stories in a totally different way of trying to understand where a client’s coming from and how to translate that to the greater public; how to say “these are problems we all face,” even though we might never have been homeless.

You also started Heckle Her. Why did you start that production company, and how does it fit into what you do now?

Heckle Her really was a vehicle for me to make my own projects as a playwright. You spend so much of your career—or, like, “career”—trying to get people to read your stuff. It’s a very slow process. You start out like, “I’m a playwright, please pay attention to me! [Laughs] Please read this script. Please come to this meeting. Please be a part of this. Please!” Now, many years later, I am in a position where people view me as being a writer and ask about my work and will come see my work, and that blows my mind because not very long ago, none of that stuff was happening for me at all.

It got to a point where it was like, either I could stop writing and find success another way, or I’m going to just make my own shit, and that’s really where Heckle Her came from. Rather than have this thing sit on my computer and never be seen, I’m going to spend some money. I’ll hustle through my day job and all of the other stuff I’ve got going on just because I want to see this thing have a life. I’m trying to have one project a year—which is about what my paycheck can afford to do [laughs]—where I’m the producer, I’m the director. Either we do something that I write, or we do something that I’m encouraging other women or people of color to write.

At a Love Me Tinder rehearsal

You seem to have a really strong balance between serious subject matter and humor in your life and work.

Yeah, my background as a writer has always been in two kind of different modes. I did the Second City training, so I was writing sketch and doing improv. And then on the other hand, I’m more interested in experimental work. Like, the last play that I did was a serious drama about a neo-Nazi terrorist who had been passing as white, and when his mixed race background was revealed, it split open this whole other story. And now I have Denim Doves, which is very slapstick. There are dick jokes in a serious conversation about female identity and value and worth. I like having that range…being able to flip between those two worlds.

Looking at your plays Am I White and Denim Doves, it seems like there’s a lot about creating an identity, breaking down an identity, having a fluid identity, and to me that’s very like interesting. Could you maybe talk a bit about how identity plays into your work, and then how it is related to your experience with your own identity?

Oh yeah, I think that’s probably the clearest link that exists in terms of my personal life and the kind of writing that I do. I don’t have an autobiographical piece yet, although that might be interesting because I do have a really unique upbringing that no one else has, and I know it’s weird, but to me it’s so normal that I’m just like, “Whatever, I’m sure people understand what it’s like to have siblings that are all special needs and we’re all adopted and all different races and we grew up in this really alternative, postmodern family. Everyone knows what that’s like!” [Laughs]

Wow, you should have an autobiographical work! I would watch that. [Laughs]

Yeah, and then when I see families that are clearly all from the same genetic material—they all look alike—it’s like, “Oh, woah. That’s weird.” [Laughs]

But yeah, I grew up very much feeling like an outsider. I’m talking about the 80s in Texas. I’m mixed race, my parents are both white, and I don’t look like anyone in my family. I’m one of the only siblings that’s fully able-bodied. So a lot of explaining was expected of me as a young kid. Like, “Hey, why don’t you look like this person?”

In terms of my journey with my identity, it’s been quite a journey, but one thing I always felt was this idea that your identity had to be static and be one thing, one box. That just didn’t line up with the way my life felt, even though I didn’t really have the language for it as a kid. For me to pick one thing…especially race, there was a lot of pressure growing up because I look very ambiguous racially. I look like maybe I should speak Spanish, and I don’t. My hair’s absolutely African American, and I’ve always—except for a brief period of time—worn my hair natural, and there are of course a lot of opinions and judgments about that. The world had this expectation of me to pick a singular identity that would stay the same, and yet my experience moving through the world was that it’s always fluid.

Am I White production still by Erica Nix and Denim Doves in rehearsal

In my art practice now, I’m looking at stories and characters that are also struggling in a world where their identity was expected to be fixed, and seeing the fallacy or the ways that that can be really limiting, restricting and almost absurd or extreme. This idea that you’re always going to be this one thing throughout your entire life and that’s never going to change, never going to be shifted or transformed by the people in your life, the experiences you have…it just seems really silly to me. Yet we see the idea that you might be both things—that you might be one thing and another thing—as being two-faced or not true. But the way the world moves right now, it’s such an advantage to have that flexibility and resilience and adaptability.

I’ve been drawn to stories like that, for sure. The more serious stuff that I write about is about that conflict of how do you navigate through that world, especially in Am I White. The character knows both of his parents. He knows his biological reality, and yet he’s made a choice to identify as only being white. That’s based off of a real guy. My play takes a totally different turn with it. It’s very dark and there’s not a lot of hope or options for redemption in that world, unfortunately. In the real world, that guy’s alive and he’s kind of renounced his past in that way, although he still has some really limiting ideas…I was pen pals with him. He’s still serving a prison sentence right now for conspiracy terrorist stuff and having guns on him and all kind of crazy shit. He’s spent most of his life in prison at this point, and he was, I think, just excited that someone was interested in telling his story, even though I’m telling it totally wrong [laughs]. He was very clear with me, like, “You’ve got it wrong. You’re an idiot. This is what happened.” Which makes sense. If I’m co-opting your story or inspired by it, you’re going to have an opinion about that.

Am I White production still by Erica Nix

It must be really strange to talk to the real person that lives at the center of this imagined world you constructed.

Absolutely. Am I White took about ten years, on and off working, before I finally had something that I felt like we could put out in the world. It wasn’t until the last five years that I heard from him. Up until that point, all that I knew about him was stuff I found on the internet, and I just sort of let my imagination go. So I got this email from him that was like, “Uh, I know you’re writing about me, and you’ve got it all wrong. I’m not an Aryan Brother. I’m from the White Order of Thule.” [Laughs] And I’m just like, “Really? Same difference. It’s all white power shit.”

At the time, I was like, “I don’t want to talk to this guy. He seems crazy. I don’t even want to open this. I don’t have space in my life for this.” Then, I had a turning point where I realized it might be an interesting conversation because he was writing a memoir. Maybe there will be something interesting in our exchange. We’ve had such completely different lives, such completely different understandings of our identity. If I could have this conversation in a safe way, then I was open to it. I had to set some boundaries in communication, like, “Look, I’m writing a piece of fiction. I’m glad you’re writing your own story. I think you should write your own story. You’re the person to tell it. But understand that I’m going to write what I’m going to write, and it’s going to be a piece of fiction.” Once we had that frame, it opened us up to being able to talk.

Then, he sent his memoir to me. It’s 600 pages. So I went from just knowing about someone from reading on the internet to, like, here is your main character giving you ages 0-32 in a 600-page PDF. [Laughs] It really blew my mind.

Did he ever read or see your play?

I did send him a copy of the play. He has read it, and he hates it. [Laughs] He’s so opinionated abut the way he’s represented, which I get, especially because the media was the one to reveal his identity. He already had this adverse experience with someone taking away his story before he could tell it. I understand where he’s coming from with that. Even though there are many things we do not see eye-to-eye on.

Were you able to learn anything from him about defining identity—even if it’s like what not to do—or find any sort of unique connection beyond just learning more about him?

Oh, absolutely. My play picks up from when he first got picked up and his relationship with his girlfriend. His girlfriend had no prior criminal background, and she renounced her views when his identity was revealed. She was like, “I love you, and you’re not just white, so that changes everything for me.” And he rejected her. He said, “You’re not really a white power activist if you accept me.” So there’s this heartbreaking love story in the middle of this crazy conspiracy trial.

For me, reading his words about that, and the way he talks about his girlfriend were really interesting because he seemed like this bigger-than-life character—like…where’s the vulnerability? Where’s the soft point? It was really hard for me for so many years to see eye-to-eye with this person. I was just looking for an entry point. What could I emotionally connect to? My guess was the girlfriend. I guessed that this girlfriend was a true love or opened something up for him. He talks about how they had a specific plan. The plan was always that if one of them gets picked up by the police, the other just runs and disappears. They don’t try to stay for the other person. But in this human moment—she was the one exchanging the counterfeit bills, and the police officer was behind her—rather than leave like he was supposed to, he felt for her and stayed and got picked up, too.

You hear about somebody like him and you think he could have hurt a lot of people, and yet, there is this capacity for love and connection. Which is why we do these things, how we’re human. We have these soft points where we know we’re not supposed to do this thing—we’re not supposed to feel in this way, maybe—and then someone gets to you, and it just changes the whole story.

Am I White production still by Erica Nix

Am I White was really well-received, right? It seems like it started a lot of good conversations, just from the awards and the coverage.

Yeah, we did not see that coming at all! [Laughs] I think I was in the production office, pacing and crying on opening night because I was so nervous. I really don’t think about an audience until opening night. Maybe it’s a survival mechanism, but it’s actually a really crazy way to experience it. Suddenly, I’m like, “Oh my god, my dad’s going to see this. He might think this part is about him!” [Laughs]

But what was surprising to us was that people were really interested in having the conversation. There’s a lot going on, obviously, about race in the news, and people were really looking for a place to come in and have a conversation about racial identity. We were really excited that people would come because you’re basically locked in a prison cell with this character for an hour. He never leaves the stage. He’s always there. He’s not a loveable hero character.

In our theater practice, we’re trying to get you to have an experience that’s unique and in the moment—that can only happen in that moment—and the fact that people were talking about it and that it inspired this conversation…it’s not something you can design, but it’s so cool when it happens.

Yeah, that’s amazing! So not to go back to the beginning, but what first got you into writing plays and theater? How did you decide that this is what you want to do?

Well, I was always a writer, from a very young age. Always writing poetry and short stories. I was very, very introverted and always journaled. If I was upset with someone, I’d write them a letter but never send it. [Laughs] It’s just a way for me to process. In my early childhood, I experienced a lot of trauma, and writing made sense because it was a way that I could express myself and speak my mind, even if I couldn’t actually form the words. Now I can finally talk to people about my feelings without pointing to a piece of paper and being like, “Here’s how I feel!” [Laughs]

So I was writing poetry a lot, and when performance poetry was in its heyday, that was something I was really into, and it just kind of happened naturally from there. It was just a do-shows-in-your-house kind of thing. There’s this thing in Austin called Mi Casa, Su Teatro with different living spaces and studios that become theaters just for one day. It’s all about people taking art into their own hands and making it. That’s also very Austin: audiences are down. They’re like, “Sure, whatever. Put me in a costume and lead me around your backyard and talk to me in character. That’s fine.” [Laughs]

So that’s kind of where I started. I had formal playwriting classes in college, and then came home to Austin after school and was part of a company of younger artists. We all just liked each other a lot and wanted to keep hanging out and drinking and making stuff together. [Laughs]

Adrienne and musician Brian Kremer at a Love Me Tinder rehearsal

Yessssss! Mantra for life. I’m curious about what Second City was like, too.

It’s funny because I got into taking classes at Second City because I wanted to be a writer, and then I got there and they were like, “We don’t have writing teams. It’s all performance-based, and we use improv to get the sketch.” So it was kind of a let-down at first. I don’t really like being in the spotlight in that way. But I was kind of like, “When in Rome…let’s just see what happens,” and I met some amazing people—they were great. I was not at their level at all. [Laughs] I hung in there as long as I could and learned a lot.

At Second City, you’re inside this institution. You walk down the hall, and you see pictures of Tina Fey and all of these amazing people…But one thing that one of my really good friends told me was, “Remember that Amy Poehler and people like that all split off from these places because they wanted to do their own thing.” You know what I mean? It’s great that we have these big systems that have these traditions and such wonderful, wonderful history, but there’s also something to be said for the people that break away and do their own thing. That was really important to realize because while I was there, I definitely felt I was failing my team. Hearing my friend say that was a nice reminder that this is a great place to pick up the training and pick up some tools, but it’s not everyone’s path that we know as being “famous” or “successful.”

I like the way you talk about breaking out and doing your own thing, and how that makes you have to be lonely and question yourself. We have a question that I ask all the babes: did you ever have a moment of self-doubt that almost stopped you from doing what you wanted to do?

[Laughs] Yes [Laughs] Every day.

Most people say that. [Laughs]

It’s so funny because it’s so universal, everyone feels it. But even though I experience that in my own life and in my own practice, I’ll see other successful artists and think, “Man, they have it so easy. They must just wake up like, ‘I’m perfect.’” You don’t see the messy draft. You don’t see the ripple of stress that comes with making stuff. In every new project, I have to remind myself that I’m going to hate my script for awhile, and that’s normal and I’m going to get through it.

And sometimes you just don’t know. It’s an experiment, and you don’t know how it’s going to go. That’s part of it, too. You have to have a bunch of really sucky plays and pieces or songs or whatever that go out there before you find something that you like. There’s always that period of testing.

There is always that, but it’s very rarely broadcast or talked about, and so we can convince ourselves that it’s not happening to other people.

I have to say I’m really, really aware of that right now because I know how I look right now. I look like everything’s going awesome, and there are some really wonderful things happening in terms of my artwork, but in my personal life, it’s been really, really hard right now. In the last couple of weeks, I had a play open, I lost a friend to cancer, and both of my sisters went into the ER for different things. It was all like bam, bam, bam, bam, bam. Like, open a play, go to a party, and then go home and cry. But all you see on Facebook is, “Hey, buy tickets to my show!” You know what I mean?

Love Me Tinder cast group photo by Shelley Hiam

It’s hard to know how to share that stuff on a mass scale, or if it should be. Does any of that against about social media and appearances tie back to Love Me Tinder?

[Laughs] I’m in the director’s seat for that show. I just thought it would be fun to direct something. I’ve not really had a lot of experience directing, in part because with my own plays, it’d just be too much. Like, “Sit down, Dawes. Let someone else get in there.” So I just cast some people—I didn’t hold auditions or anything, I just asked people that I had worked with before or that I knew in the community—and put together this ensemble, and it’s been magic. They’re writing all of their own material. There was an opportunity to perform around Valentine’s Day, so we made the show fit that theme, but this is a group of people that could easily write a musical comedy show about garage sales, and it would be interesting and funny. Really, my job has just been to put them all into the room together and then craft and shape a little bit.

A lot of the submissions that came through talk about the ways that technology is part of our relationships. Every sketch has a song, and every song has a sketch, which is really fun. For me, as an audience member, if you can sing and dance and make me laugh, I’m sold. It blows me away, like, “No, WHAT?!” [Laughs]

I know we’re running out of time to talk, unfortunately, so let’s wrap up with the big question: Do you consider yourself successful, and how do you define success?

I would say, according to my definition, I have been succeeding at my goal, which is to make stuff that I like with people that I like. That was not always my definition of success. Before, it was like, “I’m going to have a Pulitzer by the time I’m 25!”

Coming out of school, if you weren’t in American Theater magazine, and you weren’t working with famous actors from TV and weren’t able to really make your living off of your art, then you weren’t really going to be an artist…and it had to happen very young. If it didn’t happen young, you’re out. If you didn’t get your graduate degree and you didn’t have an agent, you’re out of the conversation. And really failing at that—I mean, I failed at all of that. I did not get into school. I’ve tried twice, and I might try a third time, but at this point I’m doing the things that I wanted to do. There was definitely this turning point for me where I had to give up this grander idea of what I thought success was, as defined by the way other people’s pasts are, knowing that meant that I might not be recognized and I might not be able to make this my only job. But if I have to have a day job for the rest of my life…that’s actually something I’ve always anticipated. The idea of not working a 9-to-5 and then going home for an hour to eat [laughs] and then going to the coffee shop and writing until 10 or 11—that’s always something I knew was part of the work. I realized that the act of making things is what I love, not the expectation of recognition or success.

Once I shifted my point of view in that way, I didn’t have to wait for someone to open the door for me. I didn’t need someone’s approval to make a piece of work. If I want to make a piece of work, I’ll just make a piece of work, and yeah it comes out of my paycheck or my savings, but at the end of the day, I got to make the thing, and that is more valuable and important to me than waiting around for someone to pay attention. I’ve never been successful in that way. I’ve been most successful when I do my own thing, my way. If you compare my career to someone else my age, they would have the agent, they would have the graduate degree, they would have the big productions done all over the country or a show that’s touring or something like that—and those are definitely aspirations—but I’m really happy with the way Am I White was out in the world. I was so happy and so pleased with how that all went down. My friends all got awards or recognized for their work, and that was great to see.

Adrienne winning an award for Am I White with best friend Jenny Larson

I still have no idea what happens next. I’m no longer on this path of, like, “bigger and better” and “the next project’s going to be this and then I’m going to do this”—trying to plot each thing as if I’m trying to follow a certain prescription for success instead of just seeing how I feel. [Laughs] Where’s the enjoyment or the sense of surprise? If you plan too much, you don’t allow for that sort of trickster spirit of surprise. You don’t know who you’re going to sit down next to at that coffee shop and or what discovery you might make just out on your own, living your life.

So, I don’t want to say I’m successful because that doesn’t feel true, but am I happy with the way my path is going and where am I right now? Absolutely.

You can learn more about Adrienne’s work on her website, keep track of Heckle Her on Facebook, and get tickets to Denim Doves here or Love Me Tinder here. Denim Doves runs on the Salvage Vanguard main stage until February 13, and Love Me Tinder is on stage from February 10-13.

No Comments