“I should do more site tours at midnight with a flask of whiskey.”

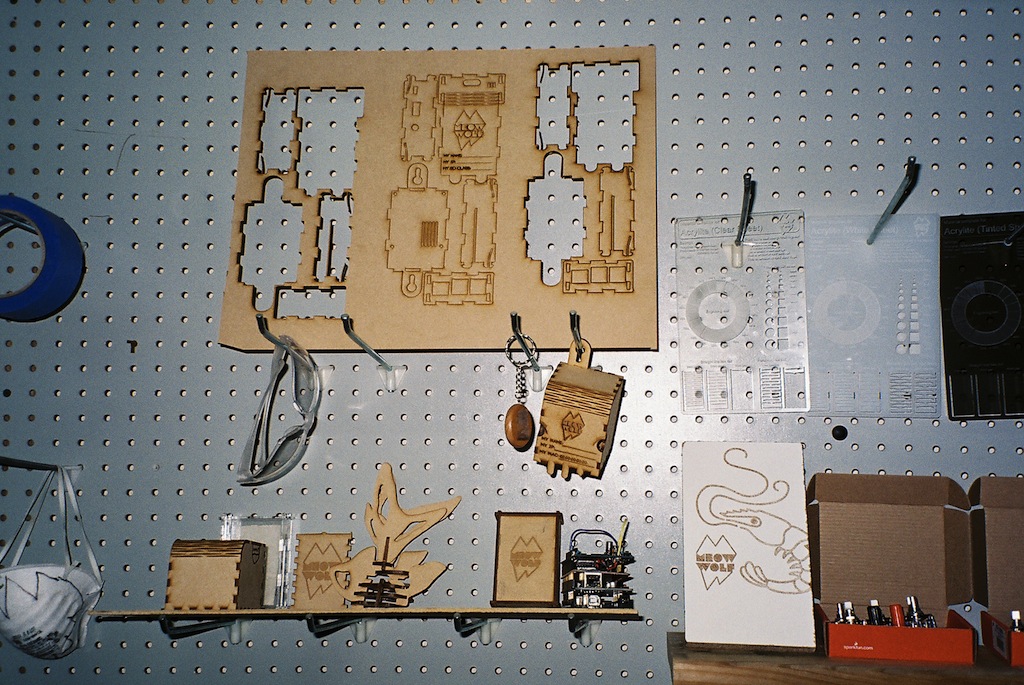

By this point in the night, we are buried deep in the imaginings of Santa Fe art collective Meow Wolf with one of its founding members, Corvas Kent Brinkerhoff II. Sipping from a small silver flask, we have traversed Meow Wolf’s major workshops, empty except for Golda Blaise. Blaise, another Meow Wolf artist, was logging late-night hours creating tiny, spiky sea creatures out of a strange, plastic goop. The scenes inside the workshops were haunting in the near-stillness. A disembodied eye that will later be inserted into a watchful forest of aspen trees sat lazily on an orange chair. A half-built tree house loomed over spiraling chunks of cardboard. The skeleton of an inter-dimensional portal cast shadows of what was to come.

By daylight, dozens of artists and makers will flood the spaces, working on these parts of Meow Wolf’s latest installation like it’s their job—because, for the first time, it is. The group has been building a network of investors to finance their latest vision, including salaries and materials for participating artists, and their project has caught an interesting pair of local eyes. George R.R. Martin…yes, that one…has taken an interest. Thanks to Martin, we are now standing in a cavernous abandoned bowling alley that he is renting to Meow Wolf and renovating per their plans. According to those plans, the former home of spares and strikes will be reopening this winter as Meow Wolf’s headquarters, featuring their first permanent installation, House of Eternal Return.

We were lucky enough to get connected to Corvas through a mutual friend, New Orleans-based artist Natalie McLaurin, and swooped through Santa Fe on a recent road trip to figure out what Meow Wolf was all about. Their website describes the collective as specializing in a unique form of immersive, multimedia installation art consisting of interactive worlds wrapped around fantastic, discoverable narratives. What we found, through meeting Corvas, was a group of magic-making artists dedicated to turning their wild dream into a lasting reality with far-reaching effects.

Even beyond the meow-howl, Corvas is an inspiration. Although we had never met before, we quickly bonded over fish tacos and oatmeal stouts topped with velvet heads at Tune-Up Café, one of his favorite spots in Santa Fe. We were captivated by his tales of letting life take him where it wanted to lead him and recognized him immediately as a one-of-a-kind bona fide babe. As he told us about how he cruised the world on a motorcycle after art school and let himself be open to collective creating, he left us wanting more moments like those he described—risky, sincere, and fully alive.

Read on to learn more about more about Meow Wolf, including the new show, and hear Corvas describe his experience collaborating with other artists, Hawaii’s ups and downs, and of course, his impressions of George R.R. Martin.

After all of your travels, how did you end up in Santa Fe and meet the people that would become Meow Wolf?

I was in Santa Fe for a couple of weeks, passing through, and I met some people that would become the reason I kept coming back. That group, along with a bunch of other people that sort of jumped in the mix, became the first class of Meow Wolf.

Who is actually in Meow Wolf has evolved a lot. A lot of that first group isn’t involved anymore. Most of them moved away. Santa Fe has a really hard time retaining young people. People tend to come here because of the inherent beauty of the landscape and a sense that it’s supportive of the arts, which is true, but it’s usually not enough for a young, ambitious creative person. I got very lucky in that I found something that really worked for me. But I also really like being in the jungle or in the woods by myself. I like not being super stimulated by my surroundings.

Do you feel like Meow Wolf has or is going to change that about Santa Fe?

Absolutely. We have a bunch of people that are moving here to work on this project. That’s one of the really exciting implications of this exhibition—what it will mean culturally for Santa Fe and redefining its identify. There’s a really vibrant, super-interesting, and talented culture of artists, writers, and musicians here that are not necessarily part of the generation that made Santa Fe famous for art in the first place. It’s a new wave of people, and nobody knows it’s here. That’s a nice effect, potentially, of our project: to bring more attention to what’s going on here.

How did the collective start? Was it always designed as a collaborative art-making community?

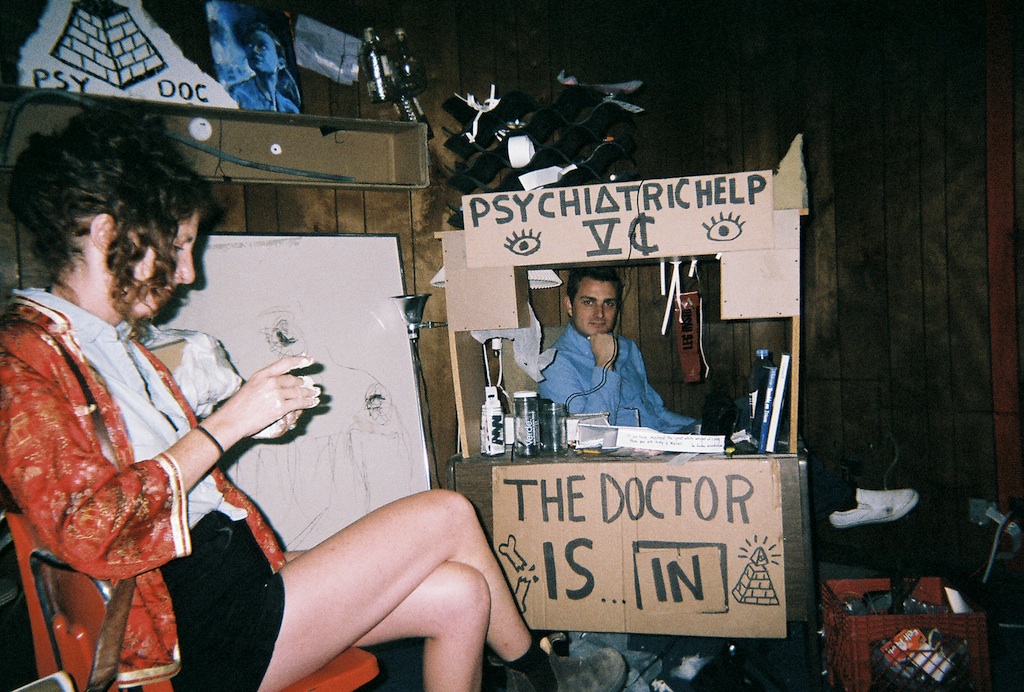

Before we formed Meow Wolf, we were throwing these little DIY punk rock shows in the basement of the house I lived in. The music was all over the map. Basically, we put on a show with anyone that was traveling through Santa Fe…that was our only criteria, which meant we had tons of horrible shows. [Laughs]

But that was kind of the impetus. We grew out of that space really fast—it could only hold, like, 18 people. This group of artists and friends gathered around a really simple vision, which was: if we all chip in a little bit of money, we could have a really rad space and do whatever we want with it. It was basically just pooling resources. The collaboration wasn’t part of the initial idea. It was just like, ‘Let’s get a space and see what happens.’

Then this collaborative process emerged out of having this collision of time and space and the creative energy of these people all in one place. These two really brilliant artists, Quinn Tincher and Matt King, did the first-ever art show at Meow Wolf. They made the whole space into a mural. Paintings went sculptural and came off the wall, and they started really activating the space. That was a big moment. A lot of creative people in the group who were thinking about their own practices realized there’s something very potent abut thinking about a space instead of a work…thinking about the work being the entire space. It’s not a new idea, but for us it hit a chord.

After that, we tried it with the whole group and did our first collaborative piece. That show was really successful. There was no money involved, but it got a ton of press and people were really excited about it. That was about seven years ago, and it’s been evolving ever since.

Do you have your own individual art practice?

Yes. The reason I went to art school was to be a painter. I’ve always been deeply committed to a life of creating and trying to tell a story. Painting was just the first thing I got positive feedback on. I got a great scholarship because of the painting I did in high school. I won some awards and got some good, positive reinforcement, so I was like, ‘Okay, this is what I’m going to be: a painter.’ Which maybe will still happen. I still like to paint. I also write music and poetry.

Are you able to make art on your own while working on Meow Wolf?

Since the beginning of Meow Wolf, I’ve been able to keep up a personal practice kind of in waves. Right now, my creative practice as it used to be is almost non-existent.

When I left school and was on the road, rambling, I had this idea about art making: that it didn’t necessarily have to mean making any thing. I tend to think about things really intensely, for better or worse, and I went through this little philosophical rabbit hole about making, which was basically this: that you’re always making. Right now, we’re making a conversation, and you guys are making a road trip…every moment is making. I got really interested in trying to connect to that desire to express myself, to be a maker of things…to connect to that through every moment, day-to-day. I had this idea that if I’m an artist, then I’m a lifestyle artist. That’s what I’m making: a lifestyle, not an object. And that happened before Meow Wolf.

That has given me a perspective on making that’s made it easier for me to take time away from my personal creative practice and still feel really connected to my sense of making and expressing. It’s a struggle. It’s a hard thing to keep balanced, and it’s probably going to get harder as we get more successful, which seems…definitely not certain, but likely at this point. In a couple of years, we could be making enough money to do only this. And there’s going to be some big existential questions at play, like, ‘Is it worth it? Is it worth sacrificing my creative vision for the greater good, or should I take a hiatus and paint?’ I don’t know the answers, but I’m anticipating all of those questions, for sure.

How do you manage your own creative vision working in a group of artists?

It’s a different kind of satisfaction from manipulating paint on a surface, and in some ways, it’s totally unsatisfactory compared to that feeling because it’s less personal. I have to diffuse my own vision in order to make it fit into other people’s. We all have to do that. Which has been part of the balancing act of Meow Wolf the whole time—how to maintain your identity and also not just argue all the time. Because if you feel really strongly about everything, you’re not going to have a very good experience working with 30 other artists. You have to learn to really fight for the few things that are most important to you and let everything else get diffused into the collective creative mind. Which is really fucking hard. It takes practice.

It’s funny how, for musicians, there’s a template for collaboration, but in art-making, there kind of isn’t. The archetypal musician is charismatic, kinetic, and they are expected to surround themselves with people. Musicians amplify each other’s talents and creative energy. The archetypal painter, on the other hand, is like, ‘Get out of my face! I’m working!’ [Laughs] There’s a totally different story around it culturally, so how it’s taught is different…everything is different.

What’s the Meow Wolf creative process like?

Our creative process is still a mystery to me. The way that our initial concepts are created is very organic. The spirit of Meow Wolf is: ideas are great, and doing things is way better. Let’s just do stuff. Let’s not get caught up in what it means or why we’re doing it. It feels good. We all have this creative synergy. Let’s keep generating work as our priority.

We’ve made a fuck ton of work, looking back, really fast. When we first started, we would have massive exhibitions every three or four months. We didn’t realize that, compared to the contemporary art world, that’s an insanely fast turnover. 2,000 square feet of completely immersive, site-specific work every three months is very prolific. That was just our instinct. It’s what we wanted to do. We’d get tired of looking at it and be like, ‘Let’s tear this down and do another one.’

It’s good to have those victories to look back on when you’re working together. To be able to remember how it all came together well. That’s what you have to connect to when you’re really not happy with a decision. There’s so many things I would have done differently if it was just me, but that’s not true because if it were just me, I never would have done any of it.

Was there a turning point where you guys realized you really had something?

We had this big show in 2011 at the Center for Contemporary Art in Santa Fe, called The Due Return. It was this giant ship modeled after a 17th century Spanish galleon, but it had been retrofit through time to be able to travel inter-dimensionally.

Over 100 artists were involved in that show. It was supposed to be open for six weeks. 2,500 or 3,000 people came just during the opening weekend. At the actual opening, there was this line of people waiting to get in that went way down the street…I’ve never seen anything like it at an art gallery. The gallery decided to extend the run of the show. It went from six weeks to three months, and by the end of the run, about 25,000 people came to see it. We didn’t have a business license or anything. We had all this cash coming in from the door, but we didn’t know what to do with it. We were literally stuffing it under a bed.

I always believed in the vision and felt that there was something special about what we were doing from the very beginning, but none of us could see that turn of events coming. That really launched our profile. We started getting all of these opportunities to show in contemporary art galleries in New York, Chicago, and New Orleans.

What’s going on with Meow Wolf right now?

Meow Wolf is transforming at this moment. It’s becoming a business. When we started making money from The Due Return, it became apparent that there’s an actual business model here. We had just been doing this thing because we loved it, and it was exciting and fun and made us all feel like we were a part of something. It was really satisfying. But we were just dumping money and time into it. So much time and money. When we would install in galleries, we had artists paying for their own materials, and then we would have to destroy it all in the end. When The Due Return was so successful, it was just a total “a-ha” moment. If we could figure out how to have a permanent exhibition that could consistently draw people to pay a small amount of money per person, we could probably keep doing this for a long time.

So now Meow Wolf is becoming a group of people that make a product deliberately for an audience that we think we understand, and we hope that audience will continue to pay us for that, so that we can keep making it. It’s a business now.

How did George R.R. Martin, of Game of Thrones fame, get involved in your current project? Tell us about George!

Once we had the idea for a permanent exhibition, the question became: where are we going to get a bunch of money to start? That was the missing piece. Who is going to invest in this? We need somebody who’s as crazy and committed to fantasy as we are.

Enter George. That’s exactly what he is. He’s spent most of his life, or at least his career, writing, at the time, unpopular, super-nerdy fantasy novels. He was the perfect person to really buy into it. We were just lucky that he’s as willing to take risks as he is and lives here in Santa Fe. He has already started similar legacy projects in Santa Fe that aren’t money-makers for him, like the Jean Cocteau Cinema—a beautiful historic theatre that he bought and reopened. I think, for him, these projects are an opportunity to feel like he’s using his success to help the community he loves and has been committed to before he became rich and famous.

Vince Kadlubek, who’s one of the six owners of the Meow Wolf company and also our CEO, had worked for George at the Jean Cocteau Cinema for a really short period of time. I don’t think it really went well, and he left really fast, but he left with George’s respect. When we found this old bowling alley—a 30,000 square foot building—and realized it was for sale, eventually it came up that George may be the closest thing we have to a perfect investor. Vince went to George and pitched our idea. George bought the building, and now he’s funding the renovations. They basically stripped it down to the shell and are rebuilding it all.

George is a very jovial, pleasant man. Just a really happy dude. Which is funny, given his stories. It must be so weird [to be George]. I’ve never been anywhere near that level of success that he’s experiencing where people feel entitled to my work. There was an article recently about him, and the reporter passed him a question from someone on the internet that was like, ‘What if you die before you finish the series?’ And his official response to that was, ‘Fuck you.’ Seriously. That question is incredibly insensitive and unsympathetic to the creative process. He can stop whenever he wants. You don’t deserve his books!

Was there ever a point when you thought this wasn’t going to work?

Yes, when we realized the next step for us was going to require a lot of money. That hung over us for…I think it was close to two years. We had the vision of what we needed to do, but we had no idea where the money was going to come from. There’s a point where that momentum gets sent in other directions. We were really close to being done with Meow Wolf.

But it’s hard to say. We probably would have kept getting opportunities to show work in contemporary art galleries, and there would have been people who wanted to do that, but they would have to pay out-of-pocket to make it happen. I think a lot of people would have gotten tired of it, and there would have been a younger class that was hungrier and more willing to bear the weight involved.

I was going to move to LA. I was pretty much done. My sister’s a TV producer there, and I was going to work on TV shows. I had a plan to move there earlier this year, then everything came together. It was like, ‘Never mind! I’m doing that!’ [Laughs]

Do you have any great stories from the road? What was your favorite place to visit?

I had a really transformative experience when I went to Hawaii. I was 23 the first time I went there. When I was dreaming of this transient lifestyle on a motorcycle, it seemed like a pretty good idea to try to be on the beach for the winter.

A couple of my friends from college and I had this plan to cruise Mexico on motorcycles together, and it just totally went to shit and fell apart. I was at my parents’ house in Lawrence, Kansas, where I grew up, broke and depressed. And this acquaintance of mine, in kind of a ballsy move, sent me an e-mail saying she was going to Hawaii in three or four weeks, and asked if I wanted to go. And that was it. That’s how I ended up there the first time. I was there for four months.

I had this crazy feeling before I left. It’s very hard to explain, but the best way I could characterize it is that it was the first time I ever had a strong intuition. I didn’t really know what to do with it or how to classify it. I have a very neat and organized brain most of the time, and I like things that fit. I knew something really big was going to happen, but I didn’t really know what the significance of having that kind of information was, and I didn’t really understand what to do with that information. It was just this very overwhelming feeling. At one point, I was afraid that I might go over there and die. That was the only way that my mind could classify that intense of an intuition. But I went, nonetheless. And what I had was this repressed crash course on how to listen to my intuition.

In my experience, that kind of information or intuition, whatever you want to call it, is much more available when I’m traveling, when I’m in a place where I’m always looking for a breeze to blow me in one direction or another. It seems like the more that you think you know how everything’s supposed to be, the less available that information is. That was definitely a bit thing I learned the first time around. I didn’t really know where I was sleeping or have any plans…I didn’t really know what I was doing there. I was basically homeless, squatting.

There were a lot of things that happened on that trip, but one of the most valuable was realizing there’s a place that anybody can go where you can just survive…and survive well. In that climate, all you need is a tarp. At that age, knowing that if I could just scrape up enough money to get back to Hawaii, I could just figure it out from that point on, was really nice. That allowed me to be pretty adventurous.

What happened? Who did you meet?

The second or third week I was there, I met this really vibrant and volatile, reckless community of former normal, middle-class mainlanders…like white American middle-class people who had run away. Basically, a very similar story to mine. They had been there anywhere from a few months to 30 years.

The dynamic of that group was very unstable. Everybody there was sort of united by this sense that they were trying to get out of their cultures. Out of the machine. And you never knew quite why. My reasons were really pure, if not just totally naïve, but some people were clearly running from a criminal past. There were lots of dangerous people.

The big island is really out of control. A friend of mine was killed. He was growing weed and was killed by what one can only assume was an organized crime ring that didn’t want the competition. But there was no official police report. His family was out there trying to figure out what happened to him, and the police weren’t cooperating. He just disappeared.

There’s this really powerful sense of grit and Wild West-type anything-goes there. It’s one of the reasons I left. I never quite felt like it was a place I could grow into. I would not want to raise a family out there. I still don’t have a family, but it’s something I think about, and it’s one of the reasons I couldn’t picture myself there forever.

Do you miss the road?

Until recently, I traveled a lot. But I’m pretty focused on my work right now for Meow Wolf. I work at 9am every morning, and that doesn’t leave a lot of room for road trips. I have this team that I’m leading, so I have to have a schedule. I’m not used to that. It’s not a natural thing for me. I don’t really like anything as much as I like traveling and also, like, just doing nothing. But it feels good. I feel like I need to give this opportunity every chance of success that I can. It’s pretty easy to just want to work all the time right now.

Keep track of Meow Wolf’s progress on the House of Eternal Return via their website or Facebook page. If you’re interested in being a part of the installation, there may be opportunities to contribute. Check those sites for more information!

Frank Rose

Posted at 22:22h, 29 SeptemberNot 3,000 – 30,000 sq. ft.!

Kerri O'Malley

Posted at 21:15h, 30 SeptemberThanks for the correction, Frank!