Let’s review what makes a bona fide babe: self-respect and respecting others, an inspired perspective of optimism, a down-ass attitude for new experiences, a killer sense of humor, a commitment to what drives you, and a keen habit of being a supportive peer.

Meet Laine Kaplan-Levenson, someone who exemplifies what being a babe is all about. Laine is one of the founders of (and now runs) Bring Your Own, a monthly storytelling event in New Orleans that has been bringing people together to laugh, cringe, listen, eat good barbecue, and drink $2 beers for four years now. While Laine provides this magical monthly resource for no personal profit, her job at New Orleans’ NPR station WWNO has challenged her to push her own storytelling and podcast-producing boundaries.

At WWNO, she crafts a weekly program on New Orleans history, tied to the city’s upcoming 300th anniversary, and is also working on a program with Eve Abrams called “Unprisoned: Stories from the System,” which has an “overarching goal of engaging people under-served by traditional media.”

I also happen to know that Laine is a solid friend, and the jokes don’t stop. Laine’s authentic approach to living and her honest, inclusive, and considerate presence in her community are why she’s such a damn babe. She’s doing things for the goddamn sake of having a good time, and she’s simultaneously gettin’ it done by pushing herself professionally and within her personal projects. While her sense of humor makes it all feel like what she does is not that big of a deal, I know that without Laine’s contributions to New Orleans, some magic would be missing from the city. Thanks, Laine, we appreciate you!

Join us as this magical lady and I talk BYO, defining and pursuing success, the importance of patience, and how to get past self-destructive behavior.

Tell us a little bit more about Bring Your Own.

Bring Your Own is a live storytelling event I run in New Orleans. It’s been going on for almost four years now, which is longer than I thought it would go. It’s a monthly event where people tell true stories in front of an audience, based on a theme. The past few themes have been “Point of No Return,” “Eyewitness,” “Secret Weapon,” and “Can of Worms.” After we announce a theme, people email me to reserve a slot to tell a story that they think fits the theme.

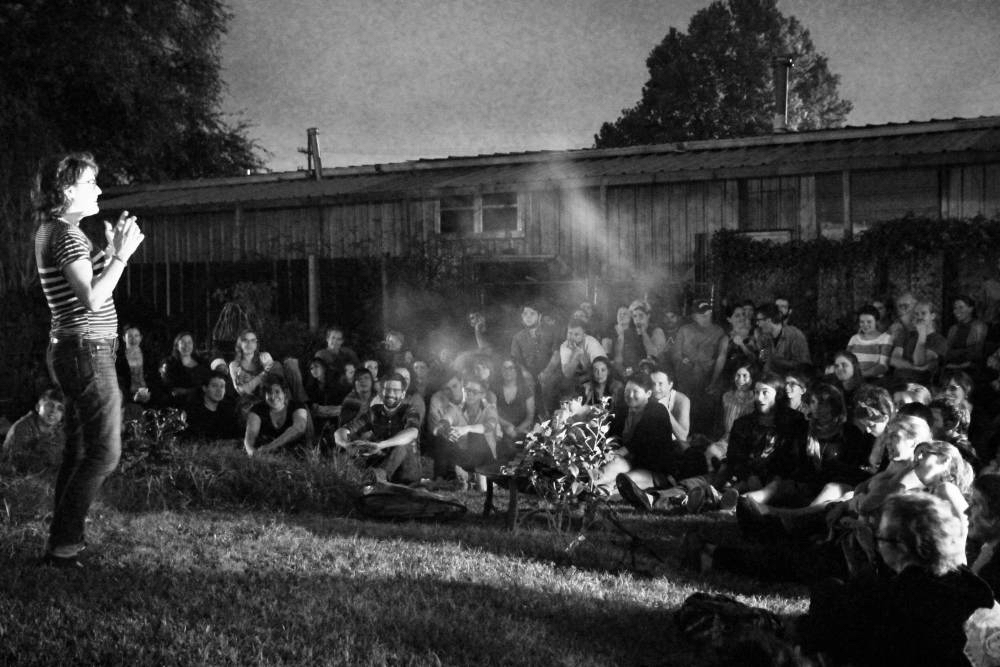

There are a few things that I think are cool about Bring Your Own. One of them is that the people that tell the stories are not polished performers…they’re not performers, period. They’re just sharing something true about themselves, and they’re doing it in a pretty vulnerable way because there’s a hundred people listening to them.

That’s terrifying!

Yeah, but afterwards, people say that being terrified was one of the reasons that they wanted to do it. It was like this test of themselves and then, for the most part, people say it felt really good.

Something I try to do to help the storyteller and the audience is to create environments that don’t feel like a performance space. We don’t try to create a theater setting or vibe because that person’s not going to be comfortable because they don’t do that, and they don’t really want to do that. I think that actually helps get more people involved and sharing stories because I’m not saying “Hey, by the way you’re going to stand on a stage, and you’re not going to be able to see anything because there’s going to be this bright light shining on you that you have no experience adapting to.” You’re going to be in a backyard, and there might be some tiki torches. People want to hear what you have to say, and we can do it without making you feel like you’re on any pedestal.

Why did you start Bring Your Own?

My friend Liam Pierce knew of this national storytelling event called The Moth. He told a story at The Moth in another city and said, “That was great! We should do that here!” So he decided to do a one-off in a friend’s backyard. It wasn’t even a party—that’s what’s nice. It was never conceived of as a party. It was conceived of as a gathering, and it’s something that was always community-focused. When he started it, it was for people that write or act to get to core of what they do, which is storytelling.

Because I was into radio, I said, “There’s no way you should do this and not record it, so let me record it.” I kind of came in as a sound engineer. We did it a few times, then we were just like, “Alright, let’s run this together.” I think Liam also realized that he had the desire to put this on, and I had the desire to give it multiple platforms, so it made sense for me to become a part of it.

What I love about Bring Your Own is that it’s not just a live event. You can go to the event and have a great experience, and that could be it. That could be Bring Your Own. But because we record it, there’s now a secondary way to access and be a part of that world. You can hear it online or as a podcast. Working at the radio station allowed us to have a partnership with NPR, so you might be driving in your car and hear it, without even seeking it out. It allowed for this kind of exponential exposure and reach in these different ways: digitally or in an old-school broadcast, which I still find so tangible…or you can throw all of that away and say, you know, it’s just an event where people come and enjoy themselves. I’m totally cool with that, too—people come to Bring Your Own sometimes not even to hear stories, but because it feels good to be there.

Four years is a long time to be running something that isn’t your job. What’s changed over the years? What makes you want to keep going?

It hasn’t changed that much, and in some ways, it hasn’t grown all that much. It’s grown in terms of reach. More people know about it. There’s a huge difference between saying the name “Bring Your Own” today and saying it in 2012, but the event still looks the same.

People come, and they look around and see 100 or more people there, and they’re always saying, “Laine, if you charged one dollar, you’d make $100. If you charged five dollars, you’d make over $500. People would still come.” But then I wouldn’t like it anymore. It’s not my job. I don’t rely on it for my income, so if I’m not doing it to eat, why would I make someone pay?

What you do to eat is pretty cool, too. What do you do in your job at WWNO, New Orleans’ NPR station?

When I started, I was reporting, doing news, which was not something that I ever thought I would do. I never took a journalism class. I didn’t think of myself as a reporter, and I didn’t think I liked to write, and I also didn’t know that radio meant that you write a lot. I recorded and produced stories about the environment for the past year, like the coastal Louisiana land loss crisis, and when my contract was coming up, they were like, “You can do that again, or we got this grant to launch a historical documentary series about the city of New Orleans leading up to the city’s tricentennial in 2018. Do you want to do that instead?” I was like, “Fuck yes. Yes!”

What’s that like? What kind of series is it?

What they decided to do, which I thought was really cool, was instead of doing a typical, PBS-style, one- or two-hour documentary, they designed a project where there would be weekly episodes that told the history of New Orleans one story at a time. That’s what I do now. I produce that series, called “TriPod.”

It’s really fun, and it’s really hard. It’s the hardest job I’ve had so far. There was a big transition for me logistically, not even getting into creatively, to having a show where, no matter what, on Thursday at 8:30 a.m. that thing is airing. And it has to be good, and it can’t have fuck-ups in it. The grind is totally different. I’ve never had to have something every week at this time no matter the fuck what. So that’s hard.

That sounds like a challenge but one that’s so beneficial for you as a person—something that motivates you to develop that discipline.

That’s really true. It’s really challenging, but in a good way. I feel like I’m back in school, too. I’m reading scholarly articles and doing research on these historical events and incidents and people and time periods. I’m reading this article that this professor at Notre Dame wrote, for example, and then I call her and interview her for an hour and make a story about it.

But that’s what’s cool. I was thinking about this recently: radio for me is the most human-based medium. The human voice, in and of itself, does things that reading words could never achieve. For me, consuming radio is a much more pleasurable experience than reading because I feel more when I hear someone’s voice.

And then, when I think about why I want to make radio as opposed to just be someone that likes to listen to radio, it’s because I like to learn, and that can be overwhelming because when you learn something or gain insight, the next thing you think is, “What am I supposed to do with that?” There’s almost a restlessness that can come with that type of expansion, and I think, for me, to have found a job that makes me do something with the stuff that I learn is a release. There’s an input, and then I make the output.

How do you prioritize your time between working your radio job, running BYO, and, you know, letting loose?

I keep a list of all the things I need to do, and I go about accomplishing the things on that last based on what I feel capable of in that exact moment. I really try to take things one at a time and give myself breaks in-between. Instead of worrying about the 248,832 things I have to do, I isolate one and only do that, and then I balance that with something for me—a walk, reading something, making a phone call. Breaks in-between accomplishments.

I also try to make sure I spend some time outside every day, and for me that’s usually through exercise, like running and swimming. I’ve realized that I also really like alone time, and I don’t need to pack my time with other people or events. So I’ve gotten better at prioritizing being by myself and letting that time be really slow, doing as little as possible. Like lying on the floor.

How do you define success?

I’ve been thinking a lot about this since the summer because there was this girl that sublet my house, and we ended up really connecting and talking until three in the morning every night. We talked a lot about stuff like this.

I know that it’s hard to accomplish, but I think that success comes from figuring out what you need to do and the things that are a part of your life. I think success is being in a place where you know that you have so much more to do, and you’re still working towards so much, and you’re also happy. You feel good about what you’ve done and what you’re doing. You wake up in the morning and feel energized by the amount that you have to do. You don’t feel plagued by it. You know that there is so much more, and instead of that making you feel terrible, it makes you feel good.

When it comes to figuring out what you want and following your passions, how do you get there? I find it has a lot to do with being fearless and courageous enough to acknowledge what you want and recognize how you may be holding yourself back.

Well, I think “fearless” and “courageous” are important words. There were a lot of years where I was not fearless and courageous professionally—that’s definitely true. I was afraid to ask for jobs, and I didn’t feel like I was a radio producer because I hadn’t studied it. I felt internally like it was right for me, but I didn’t have any way to prove it, and I wasn’t fearless and courageous enough to be like, “Who cares?!” That took me awhile.

I think what’s harder than being fearless or courageous is being patient. I think being patient is the hardest thing in the world. You can learn how to be fearless and courageous and still not learn how to be patient, and that will keep you from being happy and feeling successful. I think patience is the most important thing in the entire world: professionally, personally, interpersonally.

It inherently makes you nicer to yourself, which I think is a big problem for a lot of people including me. It’s something that almost every person struggles with, if not for their whole life, then in and out throughout their entire life. Ironically, I think you waste less time by being patient, too. You wouldn’t think that because people are so afraid of not wasting time, which I think is so linked to fear of death and mortality (which, I’m terrified of and I have been since I was born). But if you are patient, it’s harder to be bored, and if it’s harder to be bored, it’s harder to feel like you’re wasting time.

Being nice to yourself is hard, especially when there are so many things you’re trying to improve about yourself. I find that I’m being so impatient with and critical of myself as I try to make those changes.

Which doesn’t help, right?

Thank you, Laine. No, it doesn’t. [Laughs]

[Laughs] It’s just good to remember. When you go down the path of self-destructive thoughts or actions, you need to find something that will stop you in your own tracks. That’s unfortunately when we can be our strongest, most unstoppable selves: when we’re being destructive. You need to figure out the thing that stops you and makes you ask, “What is this doing? This is doing the opposite of what I want.”

How do you stop those thoughts?

More recently, it’s been trying to look ahead, even 20 minutes ahead, and say, “What is this feeling that I have about myself, this self-destructive behavior, actually going to do?” And remembering that the self-destructive behavior only perpetuates the self-destructive mindset.

Look, some people get black-out drunk and sleep with people or don’t eat or whatever. With me, it’s pretty simple: I just eat non-stop. I get anxious and stuff my face. Then, if I eat too much, I’m like no, I don’t even want to go out anymore, I’m going to stay in. And when you stay in, you don’t have an experience you would have had out in the world because you’re home alone and you feel gassy and you’re farting and you feel terrible about yourself.

So, I think more than trying to stop feeling bad about yourself, it’s to go backwards and say, “What am I doing in the first place that’s making me feel bad about myself?” and then trying to target some of those actions rather than the inner dialogue that’s so tormenting.

Can you tell us about a time where you felt like you might not succeed? Where you almost gave up?

I worked unpaid for two years for NOLA Defender with hopes and promises of not only getting paid, but receiving a salary. In the meantime, I was working part-time at a school in Kenner that was in its last year. They had no money and had actually given up. I was the technology teacher, and I ran a computer lab classroom of 25 students with learning disabilities and behavioral issues. One by one, the computers broke and were not replaced because the school didn’t give a shit anymore. So I had to teach computers to sixteen-year-olds who had been held back two or more years…without any computers. The NPR station here had no jobs yet, because they still played classical music all day, and I had applied to a two-month radio training program and was rejected.

This was all in 2011. I was about to move from New Orleans, thinking I had no opportunities here. I started thinking about jobs in advertising. I even applied for a job at Peter Mayer here in town as a copy editor and didn’t get it. So lots of rejection was happening, with no money or promise of anything changing for the better. It was rough times USA.

How were you able to get over that rough time? Why did you end up sticking with it and staying here?

I found out about Eve Abrams, who I work with now. She was one of the only radio producers that had an online presence and a website. So I emailed her, cold-called her, and said, “I want to be a radio producer, but I don’t know how, can you help me?” And it was pretty much the greatest thing that ever happened to me because she was so inviting and so enthusiastic about someone else having enthusiasm about her practice and her work. She invited me over, and I just started going to her house once a week and watching her work and watching her edit. It ended up being this really nice relationship because I watched her do what I wanted to learn how to do, and she also used me as an ear and would ask me opinions about what I thought sounded better or how the music fit in. There ended up being a give-and-take in the relationship, and we realized we offered each other different things.

But Eve is singlehandedly, really, responsible for my introduction to WWNO. She introduced me to some of the people over there because she believed in me and thought that I had a good ear. That’s when I got a very, very part-time job over there editing interviews for Poppy Tooker and her show, “Louisiana Eats.” I would make, like, forty bucks an edit. In the meantime, I got a service industry job at a cafe called Il Posto uptown. I started to do a little bit more, a little bit more, a little bit more for the station, but really slowly. Eventually, it turned into a 15-hour-a-week production position where I would do random things they assigned me for the station.

Over the course of a year, I was getting busier and busier at the radio station and had to work less and less at Il Posto. Il Posto always played WWNO in her cafe. I was working one day a week at Il Posto, and I loved it, but then I got an email from my boss who I loved—we got along really well—and she said, “Laine, at this point we hear you more on the radio than we see you at the cafe, and I love you, but you’re fired.” It was this really amazing moment of being fired, but it being a good thing. It’s really funny because, at one point, I was getting rejected from all of these things I wanted to do, but this last rejection was actually a symbol of my progress toward what I wanted to do. That’s when I realized something was actually happening.

For more on Bring Your Own, including upcoming events and recordings of past events, check out their website. You can also check out Laine’s work for WWNO here, including TriPod: New Orleans at 300 and Unprisoned: Stories from the System.

No Comments