VCS. Those three letters are probably the thing I have to explain the most about myself. “I majored in Visual and Critical Studies,” I’ll say, to which the response is usually, “Oh, cool! …What is that?”

This week’s babe, Liz Medoff, deals with the same struggle on an even greater scale, having followed up her time in the same undergrad program with a master’s. She also now works as an academic advisor at our alma mater. According to our school’s website, VCS can be defined as a department that “serves students seeking rigorous tools to explore cultural phenomena.” Within this very big box, my fellow VCS-ers and I have all developed our own working definitions. The one I find most all-encompassing is that VCS teaches critical thinking and theory and applies those principals to culture. It is a way of looking at the world and yourself with an always curious, compassionate, and analytical mind. It’s questioning powerful, pervasive ideas. It’s investigating the world we are given and using that information to pull apart what made it the way it is and to be able to imagine, radically, what could be next.

Liz applies that perspective to her work on trauma and what she more broadly calls our “emotional culture”—how society deals with emotions, both in terms of selling and repressing heavy emotional content or issues. Liz is also the woman behind Knife Play – An Online Tastemaking Endeavor, a project that has evolved from radio show to a curatorial music-and-more blog. She’s an artist who works with painting, drawing, and sound. She’s a staff writer for Dilettante Army and a yoga enthusiast. No one thing defines this total babe who seeks the connections between her passions and dreams big about how they can both work together and balance each other. Through her critical creative practices, which include writing, listening, and art, Liz encourages us to challenge the idea that we have to figure our shit out on our own and keep our struggles inside. This babe wants us to help and support each other, and she’s down to be the one to start that trend.

Join us as we talk about how to balance critical thinking with l-i-v-i-n, her definition of and work with “emotional culture,” what it’s like to advise art students, and her ideas about what’s next.

Speaking from my own experience as a VCS-er, it can be exhausting to dissect and search for meaning in everything. It can even be very overwhelming or sometimes feel overwrought. How do you deal?

I definitely think that’s kind of par for the course. After I took my first VCS class, when I was 19 and just starting college, it was like…you can’t unsee it. That’s how I felt. Like, “Shit.” [Laughs] That first class was Shawn Smith’s Girls on Film class, which is basically feminism taught through film and photography. I had never taken or studied anything like that before. It totally shifted my worldview. Then I started studying critical race stuff with Patrick Rivers, and it was like, wait…this is really overwhelming! It’s so much to process, and you start to see all of these connections. So much is becoming apparent to you.

But I really like it. I’m really engaged by trying to decipher my environment and figure out why problems exist and why people are the way they are. Yes, it’s overwhelming and problematic in its own right to just be aware of all of that stuff, but, for me, the process of investigation is really energizing and revitalizing.

I definitely take breaks. There was a period where I couldn’t do any more of the trauma stuff for awhile because it’s just…it’s harrowing! Particularly when I was writing my grad thesis, I definitely had to take a lot of steps back. But there’s something about being actively interested in resolving some of the things that contribute to trauma…it helps me make sense of the world. It’s like, okay, these are not just going to remain huge unresolved questions forever. I mean, I guess they might to some degree, but being a voice in the conversation has helped me feel a bit more grounded.

And it’s also important to just having other projects going. You’re just not a one-dimensional person who does one thing, has one interest. All of the critical writing stuff is a huge thing for me, but I also do yoga six times a week. [Laughs] I love flowers. I love ghosts. I’m interested in UFOs. [Laughs] You have to be engaged with a lot of different things to be a multi-faceted person.

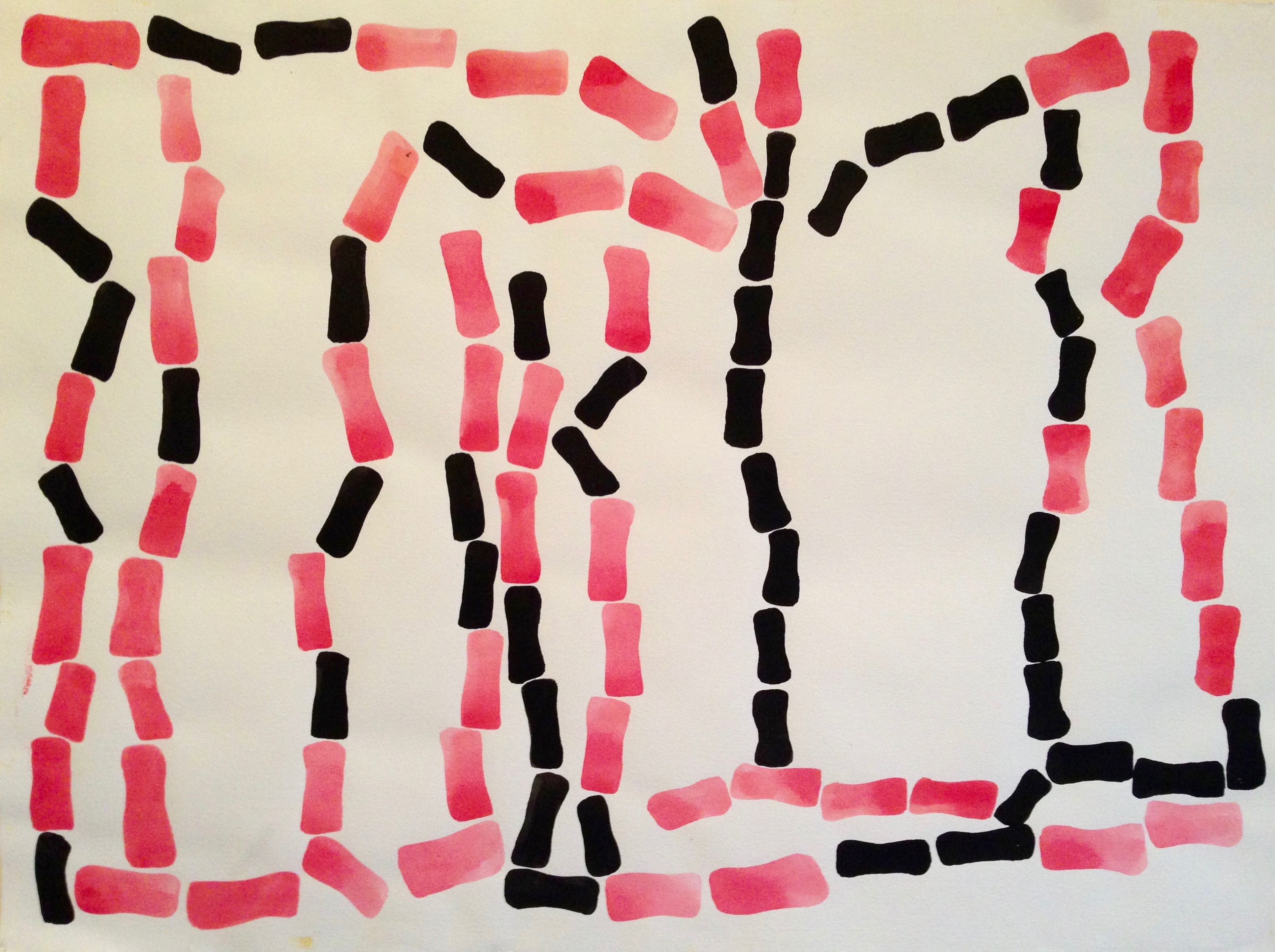

Melody by Liz Medoff

For me, that works both ways. When I’m really thinking about one idea, getting into other passions or reading can often help feed it because you find different connections in places where you didn’t expect to find them.

Definitely. If you read my first post on Dilettante Army on emotional culture, it’s looking at photography of a woman dying of cancer—there’s a woman who was diagnosed and her husband photographed the entire process—and Kim Kardashian and 9/11. In my mind, all of these things are related to this one thing, and it’s my task to try to articulate those connections.

It is completely like you said where now I’m seeing these points where things connect everywhere, and it kind of fuels itself. It’s this thing you can’t quite get out of once you start.

Talk to me a bit about your phrase “emotional culture.” What compelled you to create that term? What were you seeing in your work?

I don’t know if that term exists anywhere else. Maybe it does. When I thought of it, I thought of it as the biggest umbrella of my work. I was feeling frustrated with the conversations people would have about trauma, whether it was during critiques, presentations, or even just talking to friends about my work. I was trying to process the material I was encountering. I realized we don’t have the best vocabulary for dealing with emotions in this culture, and why is that?

At the same time, I was seeing this really emotional content sort of refracted and reflected back to me in all kinds of different ways through culture, and yet it was also this thing that was weirdly shamed. I became really interested in this tension between being constantly reminded that culture is full of emotion but also being messaged that we’re not supposed to talk about our feelings, and if you do talk about your feelings, that’s really, really bad. God forbid you be perceived as weak or “feminine.” So gender roles come into play, too.

I think we are finally starting to talk about some pretty heavy emotional content, judging by the kinds of think pieces I’ve seen online and, for example, that Brené Brown video of the Ted Talk that she gave on vulnerability. That has millions of views online, so people are wanting to have these conversations, but then we have people saying horrific things about rape survivors and other trauma survivors. You come forward with that vulnerability, and you’re publicly shamed. It’s like…which is it?

People are trying to get through it, but how do we sort of unpack these things so that we can support each other better? I think people do want to support each other and that they do want to strive for the better situation collectively, but there are so many layers to society, particularly American society, that really thwart that.

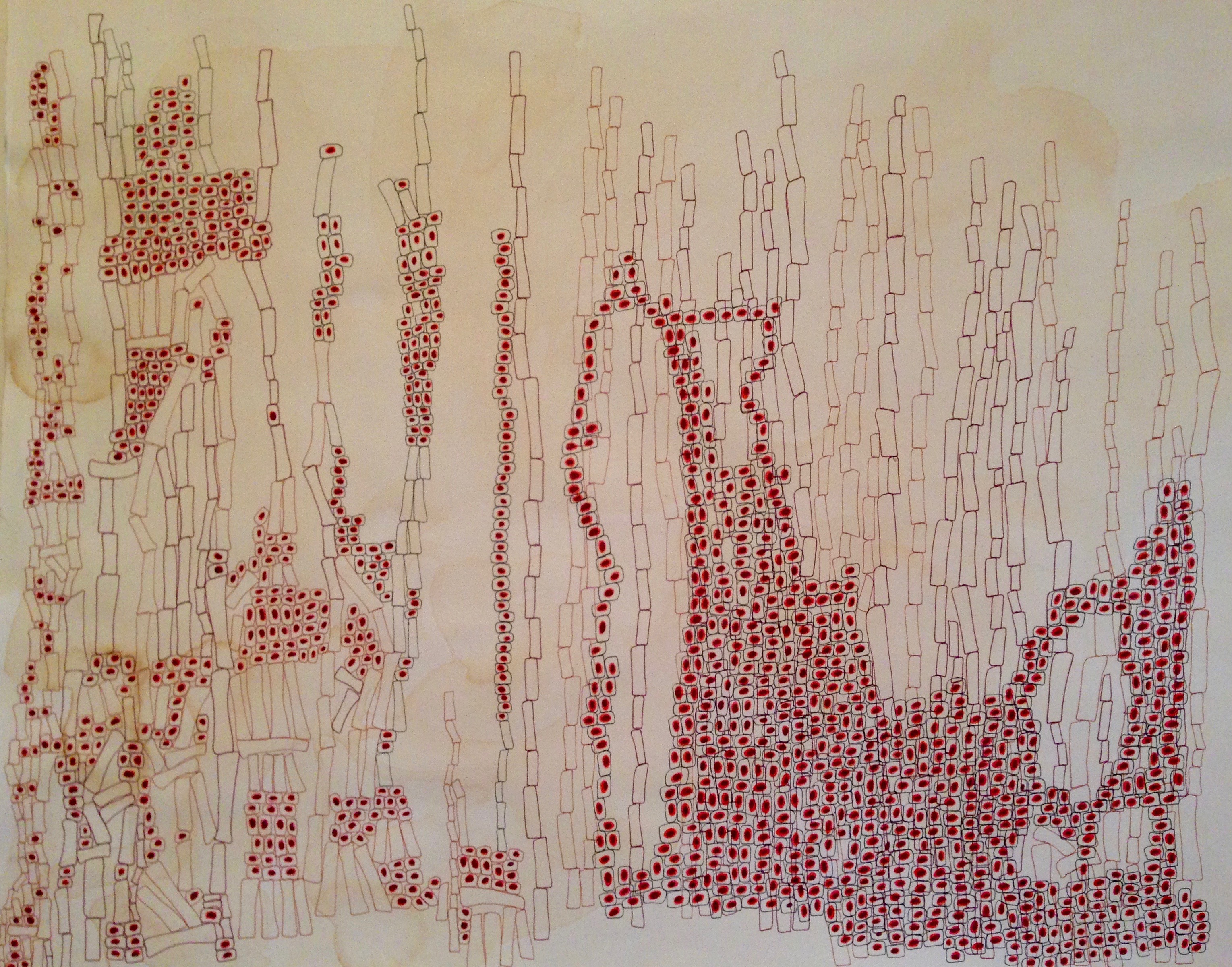

Tender by Liz Medoff

You mention the role that gender plays in emotional culture. Are men interested in your work? Have you seen how it affects that side, too?

I actually don’t think that it’s really a Side A/Side B kind of thing. It’s really all about toxic masculinity, which is where violent misogyny comes from, but it’s also where emotional oppression and repression comes from…this idea that men have be a very specific way. They have to construct their own identity based on the dominance of another person. Like…what?! [Laughs] It’s total fucking insanity. It’s garbage. I think there are a lot of men who are hurt by exactly the same system that encourages men to hurt women. It’s really devastating and sad. Nobody really wants to live like that. I’ve never heard a person say, “It is so awesome that I am afraid to connect to other people because of gender expectations.” [Laughs]

As you’ve looked at this on a cultural level, have you learned anything about dealing with trauma or emotions individually? Have you applied anything to yourself?

I mean, three years of therapy! I love my therapist! [Laughs] I think being able to embrace the difficulty, and not in a superficial, “buck up” way—that’s not what I’m talking about. But just being real about uncertainty, loss, and grief with each other and looking to each other to be supportive through that process. Because we’re all doing it.

I always tell my students, “Everybody has their shit, and if they tell you otherwise, they’re lying.” We’re all talking about it one-on-one or on this smaller level. It makes me wonder, if we could all sort of integrate a little bit more compassion, more openness…if we could all be real about trying to process our shit and could draw strength from each other and understand each other a little bit, imagine the effects of that. I mean, this is kind of the hippie in me coming through, but I believe that that’s the true way to be: to be honest, to be authentic, to be real with yourself and with other people and face the things that are hard, even if you have to ask for help. We need each other.

It seems like this is a great place to be coming from to work with students who are confused and need help. Are you able to impart things to them? Are they able to teach you things, too?

Certainly. My official title is “academic advisor,” but, in a way, that’s a terrible name for what I actually do because we have a very holistic approach. We really support students from all angles. It’s not just “here’s what’s required for your degree,” like it is in some institutions. I really get to know my students as individuals, as artists.

Initially, I thought, “Oh, I’m a person who’s always been ‘good at school.’ I can sort of demystify this process for struggling young people.” I had no idea the kind of connections I was going to make or what this job was truly going to be. It became so much more than the straightforward, academic demystification. It was much more about being able to sit with someone and talk with them, or not talk with them, as the case has been multiple times. Talking about school is the easy part. The much more interesting and kind of stakes-heavy stuff is like, “Why are you here?” What do you want to do? How do you become the person you want to be?”

And it’s been much more reciprocal than I initially realized it was going to be. My students are really interesting people. I’m always inspired by how insanely creative and talented and often just exceptionally kind they are. I get a lot out of those interactions. The way I think about it is: who did I need when I was that age? I try to be that person now.

It seems like you would have to be so strong and confident in yourself to be an advisor and a rock for these students.

Yeah, I think that’s definitely true. I have gotten pretty good at the self-care game. It’s really important, especially in any job where you even approach a counseling realm. For me, self-care is about being connected to people who are important to me. Having other stuff going on. Being involved in music. Knife Play, my “performative and curatorial blog”—that’s what I’m calling it these days—has been a really sustaining thing for me. That project is really about keeping that part of myself and my interests alive.

Tell me more about Knife Play. What was it when it started? What is it now?

It started as a radio show. I co-managed the radio station at SAIC, and then I also had my little baby, Knife Play, which started in grad school. It’s kind of embarrassing [laughs] because it was very heavy-handed at the beginning. I was reading critical theory on the air. [Laughs] Looking back on it, I’m glad I did some really dumb shit because I was sort of getting my footing around how I wanted to express myself in a public forum and what I wanted to talk about.

It started because I didn’t see what I wanted existing already. I wanted there to be a place for all of these things that I was getting into to live together, rather than having to go to 25 different places. I wanted to make it easier for someone else who maybe…I always feel like I’m a space alien and there’s no one else who’s truly like me, but let’s say they’re out there! [Laughs] That’s my target audience. That’s who I want to help.

When I first started Knife Play, I was doing more events and DJing in the real world, but with my real person job, that’s taken a backseat. Also, I got sort of fed up with DJing. It can be such a cult of personality, and I was really not interested in that, so I stopped being a person in public for awhile. [Laughs] One of my biggest values is authenticity, and I felt like I was getting too far away from what felt authentic to me, so I scaled it back and focused mostly on the online part of Knife Play. The online presence has been a really important tool to keep thinking about it, even if I can’t focus on it the way that I want to right now. It’s still a project that’s really important to me. Now, it’s like a collection or archive of what I’ve been listening to and thinking about over the past few years.

Does Knife Play tie back to the emotional culture of your critical work?

I think it’s definitely crept in over the last couple of years. Thinking about someone like Liz Harris, who performs under the name Grouper, for example. Her music is incredibly soft and quiet and small and vulnerable and beautiful and aching—of these very tender, emotional things, and she’s been important to me since I started Knife Play. My personal tastes are very much drawn from things like that, so I definitely throw them in there, even if it’s not like I specifically call out, “This is a great example of emotional culture!” [Laughs]

With all of your related but different interests, is there a dream you’re aiming for? Or are you living the dream now?

I am excited for new opportunities. I don’t know exactly what they’re going to be, but I feel pretty proud of the work I’ve done so far, so in that sense, I think I have been really successful. I’m really close to where I thought I wanted to be around the age that I am. When I was younger, I was like, “I want to go to college, and I want to go to grad school. I want to be an artist. I want to be a writer.” I’ve done those things, and that feels really great. But my primary concerns are: am I a kind person? Am I treating others well? Am I living my values? I think that we all always have work to do to be better versions of ourselves, but I feel like I’m at a good point. I’m doing those things.

Now, it’s just a question of what do I get into next? [Laughs] I’d love to see the day where there is a real-world manifestation of Knife Play. I don’t know if you’re familiar with Mount Analog in LA, but I went there for the first time a couple of years ago and was like, “Holy shit! This is what it would be if Knife Play was a real thing in the world!” They have a really interesting collection of dark, experimental records, art books, and objects, and they also do events. I was like, “Wait, these are all the things I want to do!” [Laughs] It was cool to go there and realize that someone figured out how to do this. That means maybe there’s hope for me. I’m still young. Maybe someday I can pull this together, too.

Since Knife Play is the project I’m most hoping will grow over the next couple of years, the challenge will be how do I do it on my terms so that it really is my project and my voice, and I can connect with people who believe in that. As opposed to trying to fit it into some kind of box that it doesn’t really fit into. That’s such a disservice that we do to ourselves as creative people who are trying to figure shit out. Thinking, like, “Oh, the way that I am or the way that I think is bad, and I’ve got to fix it.” I’m not sold! I’m young, and I’m feisty, and I don’t believe it yet. I’m going to keep trying and thinking about what comes next. Am I where I want to be? I’d say yes and no. But I feel pretty good about what’s happened so far. I’m going to try and keep that energy so that I can get to the next thing.

Boneyard by Liz Medoff

I really relate to what you said about making sure you pursue a project authentically. I want the same for Babe Squad! I want to create a new experience for someone—a weird experience for someone. A break from the rest of the shit that just falls in line.

Yeah! I’m so glad you said “weird.” Weird is the best! I feel so out of place a lot of the time, and it’s like, maybe I can use that to my advantage. As the outsider that I think I am…can I express that in a way that actually creates connection? If I can do that, that’s awesome.

Another sort of concrete thing that I’m really interested in doing is becoming a yoga therapist so that I can work with trauma survivors and put a lot of this embodiment theory that has come up through my academic and critical research on trauma into practice. There’s a lot of room there for overlap, so maybe someday there’s this amazing, weird collection that’s part-record store, part-art shop, and part-yoga studio. [Laughs]

I recently heard a radio news story about the positive effects of yoga on PTSD survivors, so that sounds achievable to me! Did you know about that?

I have not heard that, but I lived it. I was diagnosed with PTSD when I was 16, and yeah…yoga is a total lifeline. When you’ve had an experience that infringes on your ability to feel safety in your own body, anything you can do to create a sense of empowerment and control of your own body is good. Yoga is definitely a profound tool.

Would you be willing to share why you were diagnosed with PTSD? Or not! That’s totally okay!

[Laughs] Damn, Kerri! Well… the short version is that I had a very, very ill father, who was very abusive in lots of different ways. Some pretty horrific stuff. He passed away when I was ten, so that was a very chaotic and traumatic time—the early years of my life—but also compounding those experiences with experiences of sexual assault as an adult. I’ve had several experiences that fall into that category. Because every woman or girl that I was friends with had a story like that, I just thought, “Oh, this is just how it is.” I accepted it. It was through the process of my research and being at school and connecting with different thinkers that I realized, no, this is totally not okay.

When I was diagnosed with PTSD, I started to really learn a lot about it. Prior to that, I was sort of this fragmented, fractured person who was having all of these really intense experiences. That’s sort of…on an intellectual level, that’s what’s so interesting for me about trauma—it’s just so intense at times. Everything is so saturated, whether it’s fear or sadness or activation—feeling sort of hyper-vigilant and energized and kind of like you’re ready to run. There’s just so much feeling. Always with the feelings! [Laughs] So, yeah…I speak from experience when I talk about trauma.

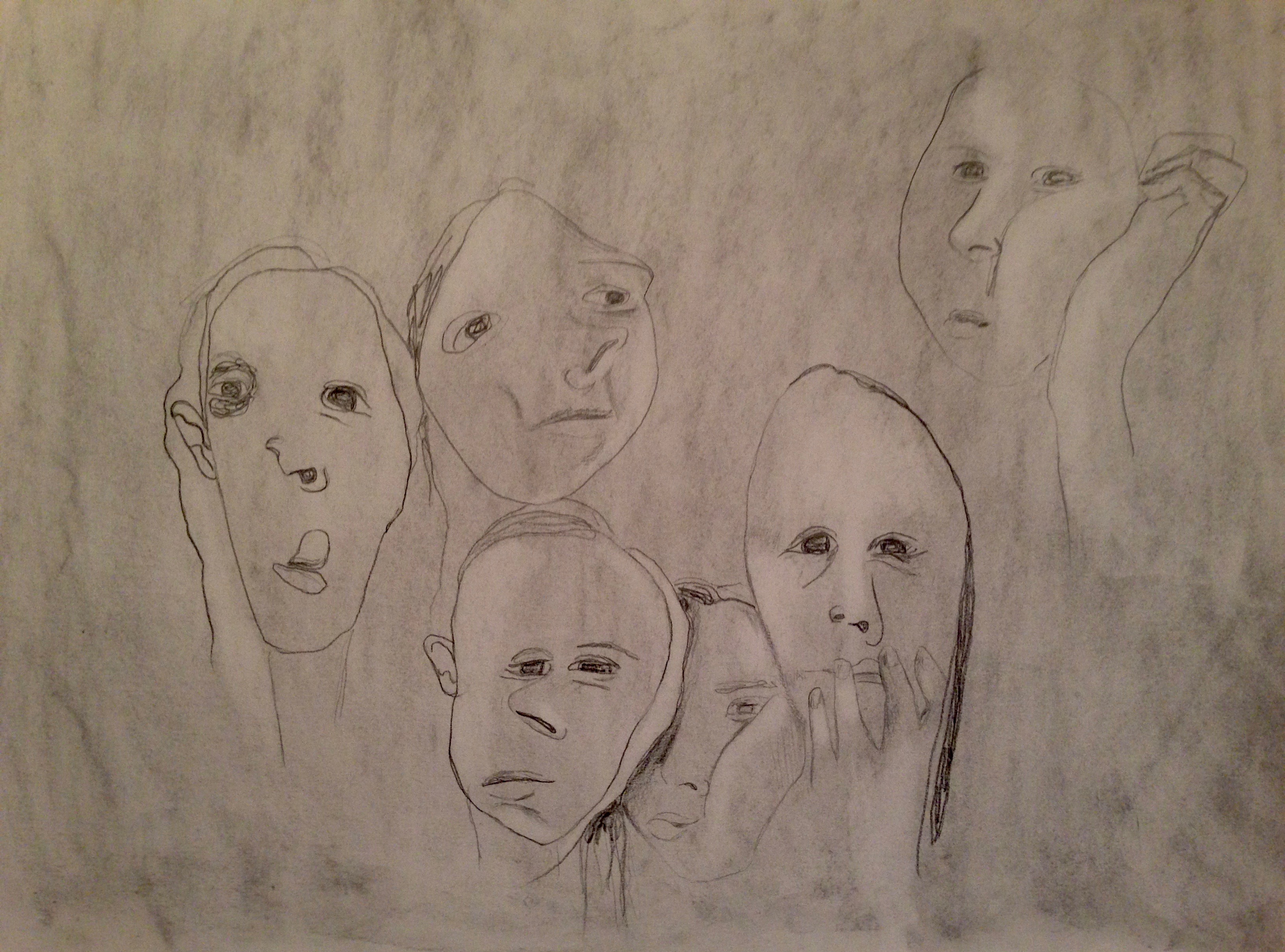

Is That What I Look Like by Liz Medoff

Did you ever have a moment where you really doubted yourself, and it almost stopped you from going where you wanted to go? How did you overcome that?

Oh yeah! For the better part of 2015—then end of 2014 into this year—I was dealing with that overwhelming feeling. I felt like my voice wasn’t valid, and that my perspective wasn’t of interest to anybody. I just sat in that space for awhile, thinking, is this really the end? Am I just going to give up on my goals now? As a person in my 20s, that seemed really impossible to digest.

Spending a little time in that dark place fueled my eventual indignance because I was like, “Wait a minute. People have written books on topics I’m really interested in. Their opinion and their voice is no more valid than mine, and mine is no less valid than theirs. They obviously figured out a way to get their ideas out there and craft an audience and connect to those people and share their ideas. So there’s probably a way for me to do that.” Everybody has something unique to contribute. No two people see things in exactly the same way.

So I dipped my toe back in the pond. I got real with myself. I realized then that I don’t know what I’m doing right now, but I’ve got to just start getting back into research, into making art—I took a break from drawing for awhile—and really getting back into a small-scale daily practice. Trying to, after a pretty dark time, stitch back together some of these things that are really important to me and just have something to show for it. Once I started seeing these small things that I made in front of me, I was like, okay, you’re doing something! [Laughs]

How do you define success?

I think success is living by your values. Success is being able to feel, at the end of the day, like I did the best that I could do with the information I had…and sort of leaving no stone unturned in terms of effort and investigation. It’s not about having a perfect outcome. It often looks different when you’re finished versus what you expected when you started. Did you go through that process and meet your challenges head on? Were you brave? Were you confident? Did you try? Were you a good person? What are my priorities as a person, and am I aligned to those on a pretty regular basis?

We all have moments where we do something that’s not in line with our values, and we feel icky about it. The best thing you can do is acknowledge that, learn from it, and move on. But don’t make one mistake and just decide that the whole show is over. When I encounter loss or disappointment, I try to sit with that as much as I need to and process it so that I can eventually digest it and move on. Integrate that and don’t let it completely derail what you’re trying to do. I would hope that what I’m trying to do is a lot bigger than a momentary shit show. [Laughs] Even if the shit show lasts for a couple of months…or even a couple of years, who knows?!? We go through really difficult stuff, but it is temporary. Eventually you come out of the other side somehow. I have lived through some crazy shit, so I will definitely attest to that!

You can read Liz’s writing on Dilettante Army, and follow Knife Play here. Liz also has an essay published in Mapping Generations of Traumatic Memory in American Narratives.

No Comments